-

In Memory of Rebarcock.

As we navigate life without Pat 'Rebarcock.' Flood, who passed on Sept 21, 2025, we continue to remember the profound impact he had on our community. His support was a cornerstone for our forum. We encourage you to visit the memorial thread to share your memories and condolences. In honor of Pat’s love for storytelling, please contribute to his ‘Rebarcock tells a story’ thread. Your stories will help keep his spirit alive among us.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Master Thread Dance Your Cares Away/Fraggle/Law Abiding Citizens

- Thread starter Bryan74b

- Start date

Master Threads.

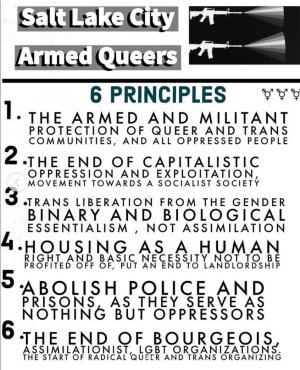

Grow the fuck up. This is what is out there. Is there an answer?

These stupid people will not admit that they are in a liberal death cult. They cannot deal with anyone that doesn’t believe every single thing they do.

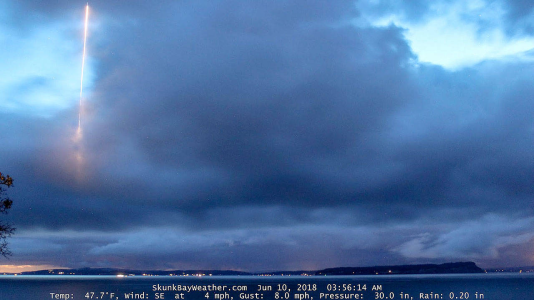

WHO shot a missile at AF1? I do not remember hearing about this.

Supposedly fired a missile at af1 during his first term in Hawaii area

Alaska?Supposedly fired a missile at af1 during his first term in Hawaii area

Supposedly near or from Whidbey Island off the coast of Washington state. Also, supposedly on his first summit meeting with rocket man. Of, could have been complete bullshit. We are never told the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.Alaska?

Of course - right when AF1 was in the area headed to Korea

Lots of Q posts regarding Red October

www.whidbeynewstimes.com

www.whidbeynewstimes.com

There was a mysterious object seen over Whidbey Island that appeared to be a missile launch, but the military confirmed it was not a missile. The object was captured by a weather camera, and experts suggested it could have been something else entirely, as there are no missile capabilities at the nearby naval base. Military

Military Patch

Patch

Lots of Q posts regarding Red October

Curious photo fueling speculation | Whidbey News-Times

Base says no rockets were launched on Whidbey

There was a mysterious object seen over Whidbey Island that appeared to be a missile launch, but the military confirmed it was not a missile. The object was captured by a weather camera, and experts suggested it could have been something else entirely, as there are no missile capabilities at the nearby naval base.

Overview of the Whidbey Island Incident

In June 2018, a mysterious object was photographed over Whidbey Island, Washington, leading to speculation that it was a missile launch. The image, captured by a weather camera, showed a bright streak in the sky that resembled a rocket's exhaust.Key Details

Object Description

- Time of Observation: Approximately 3:56 a.m. on June 10, 2018

- Location: Over Whidbey Island, near a naval air station

- Appearance: The object appeared to be ascending, similar to a missile launch

Official Responses

- Naval Air Station Whidbey Island: Officials stated there were no missile capabilities at the base and denied any missile launch occurred.

- Meteorologist Insights: Cliff Mass, a professor at the University of Washington, noted that while the object looked like a missile, there were no confirmed military operations in the area at that time.

Speculations and Theories

- Possible Explanations: Theories included atmospheric phenomena or an object moving towards the camera, creating an optical illusion.

- Public Reaction: The incident sparked significant online debate and curiosity among local residents and observers.

Keep her talking

Imagine not knowing the difference between imports and exports.

These stupid people will not admit that they are in a liberal death cult. They cannot deal with anyone that doesn’t believe every single thing they do.

Again, why libs can't admit they're wrong on anything. First they know their base won't accept it. Two, everything else unravels. That is why they are more dangerous now than ever, it's slipping away. Also why we have to win in 26 and 28

Devil's advocate: Fire in a crowded theater

The idea that one "can't shout 'fire' in a crowded theater" as a test for limiting free speech has been largely debunked for several reasons. The original legal context was weak and later overturned, and the popular phrase misrepresents the actual quote.

Misrepresentation of the original quote

The popular summary often leaves out two key qualifications from the original 1919 opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Schenck v. United States.

- The original quote: Holmes actually wrote: "The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic".

- The crucial difference: The word "falsely" is almost always omitted, changing the meaning entirely. It is a vital and protected exercise of free speech to yell "fire" if there is a real fire. The original quote also specified that the false cry must cause a panic, connecting the speech to a specific harmful outcome.

The Schenck decision, which created the "clear and present danger" test, was overturned by a later Supreme Court ruling.

- The Schenck case: In 1919, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of socialist Charles Schenck for distributing anti-draft pamphlets, ruling that his actions posed a "clear and present danger" to the war effort. Holmes' theater analogy was used to justify this limit on speech.

- The overturning of Schenck: In 1969, the case of Brandenburg v. Ohio replaced the "clear and present danger" test with the stricter "imminent lawless action" test. This new standard ruled that the government can only limit speech if it is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action" and is "likely to incite or produce such action".

Legal scholars note that Holmes' phrase was a non-binding illustration, or dictum, rather than a formal legal rule. The analogy resonated with the public because false fire alarms were a known danger that caused multiple deaths in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, it is not a legal standard for restricting speech.

What is and isn't protected

Yelling "fire" in a theater may not be a First Amendment issue at all, but rather a violation of other laws.

- Unprotected speech: If a person falsely yells "fire" to cause panic, they could be charged with crimes like disorderly conduct or reckless endangerment. If someone is killed in the stampede, it could even lead to involuntary manslaughter charges.

- Protected speech: Free speech rights do protect a person who yells "fire" in the sincere belief that there is a fire. The law's focus is on the speaker's intent and the direct, likely consequences of their words, not just the words themselves.

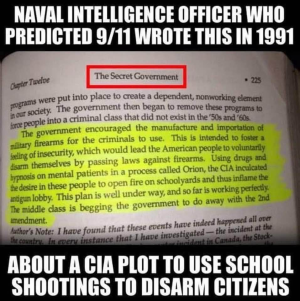

Seems very CIA to me

Gays and trannies are just (((satan)))'s useful idiots. It doesn't exist in animals. It's a myth. The only times gay acts have been observed in animals is after they've been in captivity by humans and gone insane. They're both forms of mental illness, and it's a movement Utah's governor is part of.

You're being shown four specific things about the violent Left this past week:

1. They're willing to KILL YOU for not belonging to their cult.

2. They're willing to PUBLICLY CELEBRATE one of their own killing you.

3. They're willing to RUTHLESSLY GASLIGHT everyone by denying your killer was one of their own.

4. They are aware their incoherent narrative that one fascist Nazi shot the other fascist Nazi makes no rational sense and was not going to be viable for very long.

They advanced that narrative as part of a cover and chaos campaign, because these are people who thrive on chaos, violence and deception.

You are dealing with a form of very organized and carefully cultivated...madness.

And the people who quite deliberately envisioned this madness long ago, then took specific steps to develop a 'trans community' in America with alarming speed, are now encouraging that trans community to violence as they fight a desperate rear-guard action trying to prevent their cult's complete exposure and destruction.

Those Luciferians, man.

They're the absolute WORST, man.

Good thing they didn't get to him and try to groom him....or give him the ol Utah rotisserie.

Any Republican who tries to use a left-wing terrorist incident as an opportunity to attack white supremacists should be primaried. That legitimizes left-wing ideology which was the cause of the shooting. White supremacists had nothing to do with the shooting. The "both sides" that caused it are Democrat Jews and Republican Jews.

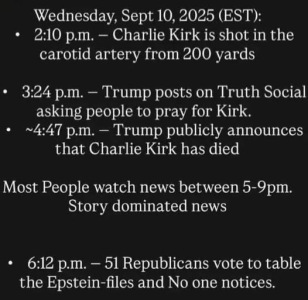

Charlie had a bullet proof vest under his shirt.You may be right and I could be wrong. Still not sure how that bullet entered the side of his neck like that. Looked like an exit not an entrance wound. Down to relying on the government. Skol brother!

Bullet hit his upper chest area and ricocheted into his neck.

Nice summary. I always view it as call to action isn’t protected speech. Well unless you’re a politician like Maxine or Obama.. and leftist media outlets.The idea that one "can't shout 'fire' in a crowded theater" as a test for limiting free speech has been largely debunked for several reasons. The original legal context was weak and later overturned, and the popular phrase misrepresents the actual quote.

Misrepresentation of the original quote

The popular summary often leaves out two key qualifications from the original 1919 opinion by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Schenck v. United States.

The legal precedent was overturned

- The original quote: Holmes actually wrote: "The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic".

- The crucial difference: The word "falsely" is almost always omitted, changing the meaning entirely. It is a vital and protected exercise of free speech to yell "fire" if there is a real fire. The original quote also specified that the false cry must cause a panic, connecting the speech to a specific harmful outcome.

The Schenck decision, which created the "clear and present danger" test, was overturned by a later Supreme Court ruling.

Analogy, not a legal doctrine

- The Schenck case: In 1919, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of socialist Charles Schenck for distributing anti-draft pamphlets, ruling that his actions posed a "clear and present danger" to the war effort. Holmes' theater analogy was used to justify this limit on speech.

- The overturning of Schenck: In 1969, the case of Brandenburg v. Ohio replaced the "clear and present danger" test with the stricter "imminent lawless action" test. This new standard ruled that the government can only limit speech if it is "directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action" and is "likely to incite or produce such action".

Legal scholars note that Holmes' phrase was a non-binding illustration, or dictum, rather than a formal legal rule. The analogy resonated with the public because false fire alarms were a known danger that caused multiple deaths in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, it is not a legal standard for restricting speech.

What is and isn't protected

Yelling "fire" in a theater may not be a First Amendment issue at all, but rather a violation of other laws.

- Unprotected speech: If a person falsely yells "fire" to cause panic, they could be charged with crimes like disorderly conduct or reckless endangerment. If someone is killed in the stampede, it could even lead to involuntary manslaughter charges.

- Protected speech: Free speech rights do protect a person who yells "fire" in the sincere belief that there is a fire. The law's focus is on the speaker's intent and the direct, likely consequences of their words, not just the words themselves.

Who got to Massie

The equivocating by all the repube pussies is mind blowing.

You don’t get on Commie News Network by having high moral standardsLooks like AIPAC is sending a message

That is what they are saying. I don't want to see it again but someone should do a slow motion frame by frame review. To see where the initial impact of the bullet was on his vest.Charlie had a bullet proof vest under his shirt.

Bullet hit his upper chest area and ricocheted into his neck.

Education was one of the pillars identified by Marxists to take over. They couldn’t figure out how Democratic countries would survive after all the attacks. They realized Education would replicate to the next generation, so for last 100 years uts been their goal to takeover education.

Education was one of the pillars identified by Marxists to take over. They couldn’t figure out how Democratic countries would survive after all the attacks. They realized Education would replicate to the next generation, so for last 100 years uts been their goal to takeover education.

And they have. For quite some time now

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 609

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 346

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 56

- Views

- 5K