-

In Memory of Rebarcock.

As we navigate life without Pat 'Rebarcock.' Flood, who passed on Sept 21, 2025, we continue to remember the profound impact he had on our community. His support was a cornerstone for our forum. We encourage you to visit the memorial thread to share your memories and condolences. In honor of Pat’s love for storytelling, please contribute to his ‘Rebarcock tells a story’ thread. Your stories will help keep his spirit alive among us.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Master Thread Dance Your Cares Away/Fraggle/Law Abiding Citizens

- Thread starter Bryan74b

- Start date

Master Threads

They won't send a single muslim but will send native born males who actually love their countries. It's blatant treason.

That’s the plan. Eliminate white peoples….

The nasty nati

That's why they call it Cincinasty.

Clinton security detail?

ShaolinNole

Legendary

Would it be insensitive for me to say she is a little long in the tooth for someone to be risking a billion dollars over? Jes sayin, she is no spring chicken.

The concerns about generative AI echo familiar fears about transformative technologies throughout history. Let’s put this in perspective. In 1957, calculators began replacing slide rules. Critics warned they’d erode mathematical reasoning, leaving engineers and scientists intellectually diminished, overly reliant on machines for basic computations. Yet, calculators didn’t destroy intellect—they freed it, enabling focus on higher-order problem-solving, accelerating innovation in fields like physics and computing. Today, we don’t mourn the slide rule; we celebrate the progress it enabled.The speaker discusses concerns about AI's societal impact, referencing The Age of AI by Eric Schmidt and Henry Kissinger. They warn that AI could create a divided society, with a small elite controlling AI systems and a larger group subject to its decisions, potentially losing autonomy due to "cognitive diminishment" from over-reliance on AI. This could lead to people losing the ability to make decisions or create independently, as AI takes over tasks like art, writing, and navigation. The speaker highlights risks of AI in critical systems, such as humanitarian aid distribution or military targeting, citing examples like inaccurate facial recognition and AI-driven surveillance tested in conflict zones. They question the motives of figures like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk, noting their ties to surveillance tech (e.g., Palantir) and government contracts, suggesting their actions contradict their libertarian claims. The speaker criticizes the influence of Silicon Valley and the "PayPal mafia" on media and AI development, warning of potential manipulation through data collection. They advocate for resisting this trajectory by maintaining personal creativity, local empowerment, and skepticism of centralized systems, urging people to avoid outsourcing their skills and decisions to AI to prevent a "posthuman" future of control and dependency.

Rewind further: in the early 1900s, cars replaced horse-drawn carriages. Naysayers decried the loss of traditional skills, the disruption of livery jobs, and the chaos of mechanized transport. But cars reshaped society for the better—expanding mobility, fostering economic growth, and creating new industries. The buggy whip makers adapted or found new roles, and society thrived.

Now, consider generative AI. The author warns of cognitive diminishment and elite control, but these fears assume people are passive, incapable of adapting. Just as calculators didn’t end math, AI won’t end creativity—it’s a tool, not a replacement. Artists and writers are already using AI to augment their work, not abandon it. The examples of AI misuse—flawed facial recognition or surveillance—are real, but they reflect implementation failures, not the technology’s essence. Cars crashed, yet we didn’t ban them; we improved safety standards. Similarly, AI’s risks call for regulation and ethical design, not rejection.

People can question the motives of tech leaders, but every disruptive era has its pioneers—Ford, Edison, Gates—whose ambitions sparked debate. Their flaws didn’t negate their contributions. AI, like electricity or the internet, will be shaped by how we wield it. Rather than fear a “posthuman” future, let’s empower people to use AI for creativity, problem-solving, and local innovation, just as we did with past technologies. The answer isn’t resistance—it’s responsibility. We’ve navigated these shifts before. We’ll do it again.

Simpson's are like fucking prophetic every time!

I saw this reported and it looked too insane to be true. One person in the comments said that its the glass reflecting onto concrete and blacktop creating just superheated areas. Freaking wild though.

That's been the problem with many of these colored glass buildings. One city in England had a building doing this and they had to exchange the windows with less reflective ones.

Goldhedge

Legendary

Thread by @DNIGabbard on Thread Reader App

@DNIGabbard: 🧵 Americans will finally learn the truth about how in 2016, intelligence was politicized and weaponized by the most powerful people in the Obama Administration to lay the groundwork for what was essenti...…

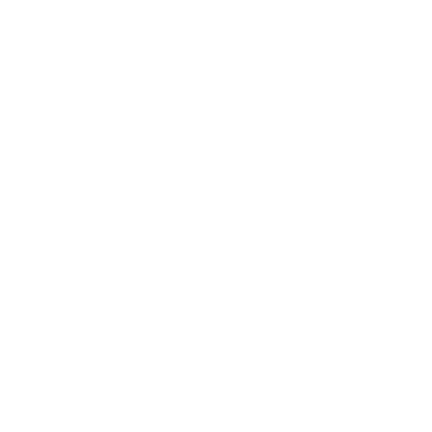

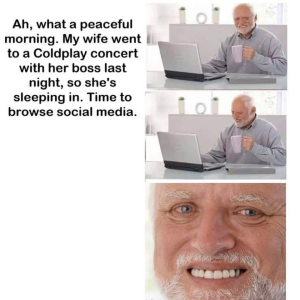

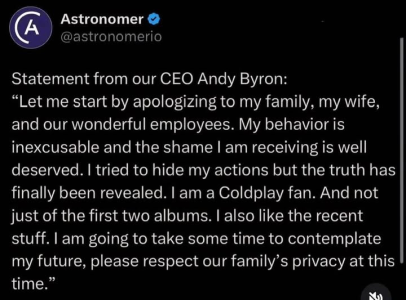

Maybe they are just really good f-buddies. Wife and kids are the home life. She's the not at home Cold-Playtoy.Would it be insensitive for me to say she is a little long in the tooth for someone to be risking a billion dollars over? Jes sayin, she is no spring chicken.

Every one of these memes, photos or other posts showing them makes the cash registers ring at the wife's lawyer's office. Word of the day - humiliation.

Motherfvckers

You want ice cream go get Braum's or other brand. You want a chocolate dipped cone you go to DQ and don't care if it's ice cream.

They are wrong about kamala

View attachment 236743

Lisa is a little brainwashed retard

What Snowden revealed about Obama spying on journalists and political enemies eclipses anything Nixon ever did. This just escalates the criminal behavior to a unpresidential level.

Tl;dr other than you proved intellectually diminished.The concerns about generative AI echo familiar fears about transformative technologies throughout history. Let’s put this in perspective. In 1957, calculators began replacing slide rules. Critics warned they’d erode mathematical reasoning, leaving engineers and scientists intellectually diminished, overly reliant on machines for basic computations. Yet, calculators didn’t destroy intellect—they freed it, enabling focus on higher-order problem-solving, accelerating innovation in fields like physics and computing. Today, we don’t mourn the slide rule; we celebrate the progress it enabled.

Rewind further: in the early 1900s, cars replaced horse-drawn carriages. Naysayers decried the loss of traditional skills, the disruption of livery jobs, and the chaos of mechanized transport. But cars reshaped society for the better—expanding mobility, fostering economic growth, and creating new industries. The buggy whip makers adapted or found new roles, and society thrived.

Now, consider generative AI. The author warns of cognitive diminishment and elite control, but these fears assume people are passive, incapable of adapting. Just as calculators didn’t end math, AI won’t end creativity—it’s a tool, not a replacement. Artists and writers are already using AI to augment their work, not abandon it. The examples of AI misuse—flawed facial recognition or surveillance—are real, but they reflect implementation failures, not the technology’s essence. Cars crashed, yet we didn’t ban them; we improved safety standards. Similarly, AI’s risks call for regulation and ethical design, not rejection.

People can question the motives of tech leaders, but every disruptive era has its pioneers—Ford, Edison, Gates—whose ambitions sparked debate. Their flaws didn’t negate their contributions. AI, like electricity or the internet, will be shaped by how we wield it. Rather than fear a “posthuman” future, let’s empower people to use AI for creativity, problem-solving, and local innovation, just as we did with past technologies. The answer isn’t resistance—it’s responsibility. We’ve navigated these shifts before. We’ll do it again.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 573

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 318

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 56

- Views

- 5K