-

In Memory of Rebarcock.

As we navigate life without Pat 'Rebarcock.' Flood, who passed on Sept 21, 2025, we continue to remember the profound impact he had on our community. His support was a cornerstone for our forum. We encourage you to visit the memorial thread to share your memories and condolences. In honor of Pat’s love for storytelling, please contribute to his ‘Rebarcock tells a story’ thread. Your stories will help keep his spirit alive among us.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Master Thread Dance Your Cares Away/Fraggle/Law Abiding Citizens

- Thread starter Bryan74b

- Start date

Master Threads.

Most importantly is Poland doesn't let those nimrods into their country.

Fvck Ireland and their leftist elite and entertainers who want this

Their elections are rigged too.

This is my line of work now and it is a nice glossy brochure. He is creating unsurvivable mass. Their barracuda weapon has no rails to hang on in a peer war. If you need to make something go away the first time it is survivable, and not cheap. Weapons integration is a serious problem in the DOW.

Hey a few months back you said something was going to happen South of the border - what is it? when? has it happened?

TIA

And Yamamoto tossed a complete game gem in Toronto.AmericaJapan over Canada. Let's goDodgers!Rice Balls!

FIFY

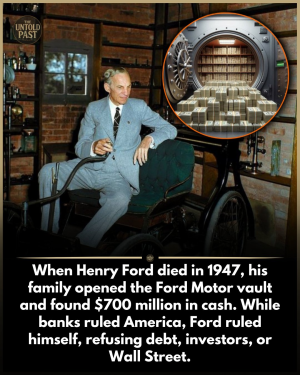

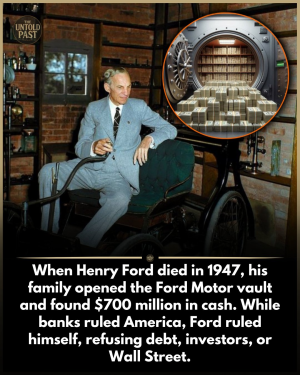

When Henry Ford died in 1947, his family didn’t just inherit an empire — they opened a vault and found a fortune. Inside the Ford Motor Company’s private reserves lay nearly $700 million in cash, untouched by banks or investors.

It was a revelation that stunned even the business world. Ford had built one of the largest industrial empires in history — and he had done it without borrowing a single dime.

While other automakers leaned on Wall Street, Ford kept his company private, funding everything internally — from the Model T assembly lines to the massive River Rouge Plant that became the beating heart of American manufacturing. He refused to take loans, issue stock, or surrender control. Banks offered influence; Ford preferred independence.

His logic was simple but radical: “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s theirs.” He wanted no part of either.

By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become a self-contained economic ecosystem — smelting its own steel, producing its own glass, even generating its own electricity. The money that flowed in from every Model T sale didn’t leave the company; it fueled the next invention, the next plant, the next experiment.

And it worked. When the Great Depression crushed competitors drowning in debt, Ford’s privately funded machine kept turning. He could slow production, pay workers, and wait out the storm — all without a single bank call.

So when his heirs discovered hundreds of millions in cash sealed inside the company’s vault, it wasn’t greed. It was the ultimate proof of Ford’s obsession with control — and his defiance of the financial world that once mocked him.

In an age when corporations danced to Wall Street’s tune, Ford marched to his own rhythm — the sound of pistons, progress, and absolute independence.

He didn’t just build cars. He built a new kind of power — one that didn’t need permission.

Would you have trusted your instincts over every banker in America — and been bold enough to fund the future from your own pocket?

It was a revelation that stunned even the business world. Ford had built one of the largest industrial empires in history — and he had done it without borrowing a single dime.

While other automakers leaned on Wall Street, Ford kept his company private, funding everything internally — from the Model T assembly lines to the massive River Rouge Plant that became the beating heart of American manufacturing. He refused to take loans, issue stock, or surrender control. Banks offered influence; Ford preferred independence.

His logic was simple but radical: “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s theirs.” He wanted no part of either.

By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become a self-contained economic ecosystem — smelting its own steel, producing its own glass, even generating its own electricity. The money that flowed in from every Model T sale didn’t leave the company; it fueled the next invention, the next plant, the next experiment.

And it worked. When the Great Depression crushed competitors drowning in debt, Ford’s privately funded machine kept turning. He could slow production, pay workers, and wait out the storm — all without a single bank call.

So when his heirs discovered hundreds of millions in cash sealed inside the company’s vault, it wasn’t greed. It was the ultimate proof of Ford’s obsession with control — and his defiance of the financial world that once mocked him.

In an age when corporations danced to Wall Street’s tune, Ford marched to his own rhythm — the sound of pistons, progress, and absolute independence.

He didn’t just build cars. He built a new kind of power — one that didn’t need permission.

Would you have trusted your instincts over every banker in America — and been bold enough to fund the future from your own pocket?

Are you being obtuse? The cartel stuff in Mexico. All of the interdiction in Southcom. What exactly are you looking for?Hey a few months back you said something was going to happen South of the border - what is it? when? has it happened?

TIA

When Henry Ford died in 1947, his family didn’t just inherit an empire — they opened a vault and found a fortune. Inside the Ford Motor Company’s private reserves lay nearly $700 million in cash, untouched by banks or investors.

It was a revelation that stunned even the business world. Ford had built one of the largest industrial empires in history — and he had done it without borrowing a single dime.

While other automakers leaned on Wall Street, Ford kept his company private, funding everything internally — from the Model T assembly lines to the massive River Rouge Plant that became the beating heart of American manufacturing. He refused to take loans, issue stock, or surrender control. Banks offered influence; Ford preferred independence.

His logic was simple but radical: “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s theirs.” He wanted no part of either.

By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become a self-contained economic ecosystem — smelting its own steel, producing its own glass, even generating its own electricity. The money that flowed in from every Model T sale didn’t leave the company; it fueled the next invention, the next plant, the next experiment.

And it worked. When the Great Depression crushed competitors drowning in debt, Ford’s privately funded machine kept turning. He could slow production, pay workers, and wait out the storm — all without a single bank call.

So when his heirs discovered hundreds of millions in cash sealed inside the company’s vault, it wasn’t greed. It was the ultimate proof of Ford’s obsession with control — and his defiance of the financial world that once mocked him.

In an age when corporations danced to Wall Street’s tune, Ford marched to his own rhythm — the sound of pistons, progress, and absolute independence.

He didn’t just build cars. He built a new kind of power — one that didn’t need permission.

Would you have trusted your instincts over every banker in America — and been bold enough to fund the future from your own pocket?

View attachment 241437

History of the Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation, one of the world’s largest private philanthropic organizations, has played a pivotal role in advancing social justice, education, and global welfare since its inception. Below is a chronological overview of its history, drawing from key milestones, leadership shifts, and major initiatives.

Founding and Early Years (1936–1947)

Established on January 15, 1936, in Michigan by Edsel Ford (son of Henry Ford) and his father, Henry Ford, the foundation was created to manage funds for scientific, educational, and charitable purposes. It began with a modest $25,000 gift from Edsel Ford (equivalent to about $550,000 in 2023 dollars). The timing was influenced by the 1935 Revenue Act, which imposed a 70% tax on large inheritances, prompting the Fords to formalize their philanthropy. Under family leadership, early grants supported Ford-related institutions, such as the Henry Ford Hospital and the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

Transition and Expansion (1947–1953)

Following Edsel Ford’s death in 1943 and Henry Ford’s in 1947, Henry Ford II assumed the presidency. By 1947, the foundation controlled 90% of the non-voting shares in Ford Motor Company, while the Ford family retained voting shares. In 1949, Henry Ford II separated Ford Motor Company’s corporate philanthropy into a distinct entity called Ford Philanthropy. To redefine its direction, the foundation commissioned the Gaither Study Committee in 1949, chaired by Horace Rowan Gaither. The committee’s 1950 report advocated transforming the foundation into an international entity focused on human welfare. In 1953, it relocated from Michigan to New York City, marking a shift from local to global ambitions.

Cold War Era and International Engagement (1950s–1960s)

During the Cold War, the foundation became entangled in U.S. geopolitical efforts. In 1950, it provided a $150,000 grant (via the International Rescue Committee) to the CIA-linked Fighting Group Against Inhumanity in West Berlin. From 1958 to 1965, under chairman John J. McCloy (a former OSS/CIA figure), it facilitated CIA funding for cultural and intellectual initiatives to counter communism. This included grants influencing global narratives, such as funding an economics program at Indonesian University that supported the 1965 coup installing Suharto. The foundation’s 1950 policy report outlined five focus areas: economic well-being, education, freedom and democracy, human behavior, and world peace.

Divestment, Leadership Shifts, and Program Growth (1955–1976)

Between 1955 and 1974, the foundation gradually divested its Ford Motor Company stock, allowing the automaker to go fully public and freeing the foundation for independent operations. In 1976, Henry Ford II resigned from the board, criticizing the organization’s large staff, outdated programs, and perceived anti-capitalist leanings. This era saw explosive growth in initiatives, including:

Modern Era and Diversification (1970s–Present)

The 1980s onward emphasized equity and inclusion. The Ford Fellowship Program, launched in 1980, has awarded over 4,000 fellowships to underrepresented scholars in STEM and humanities (sunset announced in 2022). Since 1987, it has funded AIDS responses, disbursing $29.5 million in 2010 alone. In the 2010s, under presidents like Luis Ubiñas and Darren Walker, it pivoted toward impact investing: In 2018, it committed $1 billion from its $12.5 billion endowment to mission-aligned investments yielding social and financial returns.

Recent initiatives include:

As of 2023, the foundation’s endowment stands at $16.8 billion, with $852 million in annual expenses, making it the second-largest U.S. foundation by assets. It operates globally in the U.S., Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, focusing on poverty reduction, democracy, and equity. Current leadership includes Chairman Francisco G. Cigarroa and President Heather Gerken; Henry Ford III joined the board in 2019, the first family member since 1976. Its New York headquarters, completed in 1968, is a designated landmark for its innovative atrium design.

Controversies

The foundation’s history includes scrutiny over its Cold War CIA ties, population control funding (criticized as eugenics-adjacent), and civil rights grants accused of promoting left-leaning activism. In the 2000s, it faced backlash for funding Israeli NGOs via the New Israel Fund (over $40 million since 2003), some labeled antisemitic; it apologized in 2003, tightened guidelines, and ended Israel funding in 2011. In 2023, it cut ties with the Alliance for Global Justice over alleged terrorism links.

Overall, the Ford Foundation has evolved from a family tax shelter into a powerhouse for progressive change, distributing billions while navigating geopolitical and ideological debates.

The Ford Foundation, one of the world’s largest private philanthropic organizations, has played a pivotal role in advancing social justice, education, and global welfare since its inception. Below is a chronological overview of its history, drawing from key milestones, leadership shifts, and major initiatives.

Founding and Early Years (1936–1947)

Established on January 15, 1936, in Michigan by Edsel Ford (son of Henry Ford) and his father, Henry Ford, the foundation was created to manage funds for scientific, educational, and charitable purposes. It began with a modest $25,000 gift from Edsel Ford (equivalent to about $550,000 in 2023 dollars). The timing was influenced by the 1935 Revenue Act, which imposed a 70% tax on large inheritances, prompting the Fords to formalize their philanthropy. Under family leadership, early grants supported Ford-related institutions, such as the Henry Ford Hospital and the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.

Transition and Expansion (1947–1953)

Following Edsel Ford’s death in 1943 and Henry Ford’s in 1947, Henry Ford II assumed the presidency. By 1947, the foundation controlled 90% of the non-voting shares in Ford Motor Company, while the Ford family retained voting shares. In 1949, Henry Ford II separated Ford Motor Company’s corporate philanthropy into a distinct entity called Ford Philanthropy. To redefine its direction, the foundation commissioned the Gaither Study Committee in 1949, chaired by Horace Rowan Gaither. The committee’s 1950 report advocated transforming the foundation into an international entity focused on human welfare. In 1953, it relocated from Michigan to New York City, marking a shift from local to global ambitions.

Cold War Era and International Engagement (1950s–1960s)

During the Cold War, the foundation became entangled in U.S. geopolitical efforts. In 1950, it provided a $150,000 grant (via the International Rescue Committee) to the CIA-linked Fighting Group Against Inhumanity in West Berlin. From 1958 to 1965, under chairman John J. McCloy (a former OSS/CIA figure), it facilitated CIA funding for cultural and intellectual initiatives to counter communism. This included grants influencing global narratives, such as funding an economics program at Indonesian University that supported the 1965 coup installing Suharto. The foundation’s 1950 policy report outlined five focus areas: economic well-being, education, freedom and democracy, human behavior, and world peace.

Divestment, Leadership Shifts, and Program Growth (1955–1976)

Between 1955 and 1974, the foundation gradually divested its Ford Motor Company stock, allowing the automaker to go fully public and freeing the foundation for independent operations. In 1976, Henry Ford II resigned from the board, criticizing the organization’s large staff, outdated programs, and perceived anti-capitalist leanings. This era saw explosive growth in initiatives, including:

- Media and Education: In 1951, it funded the precursor to PBS (National Educational Television). The Fund for Adult Education (1951–1961) invested over $47 million in public broadcasting, adult learning conferences, and projects like educational TV pilots.

- Arts and Humanities: It supported fellowships for luminaries like James Baldwin, Margaret Mead, and Robert Lowell, and backed regional theaters and the Fund for the Republic (1950s) for free speech advocacy.

- Reproductive Rights and Health: In the 1960s–1970s, it poured up to $169 million into global contraception programs and $1.17 million into UK in vitro fertilization research, contributing to the 1978 birth of the first “test-tube baby,” Louise Brown.

- Civil Rights and Legal Aid: From 1967 onward, it granted $12 million for law school clinics, $18 million to civil rights groups (e.g., $2.2 million to the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund in 1967), and support for Native American, Puerto Rican, and voter registration efforts.

- Education Reform: In 1967–1968, it backed New York City’s Ocean Hill–Brownsville school decentralization, sparking a major teachers’ strike.

- Arts and Music: The 1966–1976 Symphony Program invested $80.2 million in 61 U.S. orchestras to boost artistic quality and finances.

Modern Era and Diversification (1970s–Present)

The 1980s onward emphasized equity and inclusion. The Ford Fellowship Program, launched in 1980, has awarded over 4,000 fellowships to underrepresented scholars in STEM and humanities (sunset announced in 2022). Since 1987, it has funded AIDS responses, disbursing $29.5 million in 2010 alone. In the 2010s, under presidents like Luis Ubiñas and Darren Walker, it pivoted toward impact investing: In 2018, it committed $1 billion from its $12.5 billion endowment to mission-aligned investments yielding social and financial returns.

Recent initiatives include:

- Disability Futures Fellows (2020): $50,000 annual awards for disabled artists, in partnership with the Mellon Foundation.

- Creative Futures (2020): 40 commissions exploring culture amid COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter.

- America’s Cultural Treasures (2020): Over $165 million pledged for arts organizations led by people of color.

As of 2023, the foundation’s endowment stands at $16.8 billion, with $852 million in annual expenses, making it the second-largest U.S. foundation by assets. It operates globally in the U.S., Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia, focusing on poverty reduction, democracy, and equity. Current leadership includes Chairman Francisco G. Cigarroa and President Heather Gerken; Henry Ford III joined the board in 2019, the first family member since 1976. Its New York headquarters, completed in 1968, is a designated landmark for its innovative atrium design.

Controversies

The foundation’s history includes scrutiny over its Cold War CIA ties, population control funding (criticized as eugenics-adjacent), and civil rights grants accused of promoting left-leaning activism. In the 2000s, it faced backlash for funding Israeli NGOs via the New Israel Fund (over $40 million since 2003), some labeled antisemitic; it apologized in 2003, tightened guidelines, and ended Israel funding in 2011. In 2023, it cut ties with the Alliance for Global Justice over alleged terrorism links.

Overall, the Ford Foundation has evolved from a family tax shelter into a powerhouse for progressive change, distributing billions while navigating geopolitical and ideological debates.

Bet on it...

Talk about a FAFO situation….

Bet on it...

I didn't think of this but I believe this lady is 100% correct. I think of my parents, other love ones, elderly, and people thats always on their phones getting attacked.

Damn this really fires me up.

The Schumer Shutdown is really the Schumer Political Death Knell.

And no tattoos, nails, weaves

And if you can qualify for a credit card and drive a late model SUV

Are you being obtuse? The cartel stuff in Mexico. All of the interdiction in Southcom. What exactly are you looking for?

Nope, not being obtuse. I’ve just been on and off the board sporadically because I’ve been taking care of my dad and busy at work doing mortgages, cost segregation and a new project.

I figured that was it. I just didn’t want to miss out on anything. Have a great day!!!

In Holland you cant advertise with pharma stuff. Or tabacco, or weed for that matter.

I was extremely surprised when I was watching tv in the US and I was prompted with the "Buy our Chemo now" advertisement. Super wicked.

Ford also wrote a book about Jews.When Henry Ford died in 1947, his family didn’t just inherit an empire — they opened a vault and found a fortune. Inside the Ford Motor Company’s private reserves lay nearly $700 million in cash, untouched by banks or investors.

It was a revelation that stunned even the business world. Ford had built one of the largest industrial empires in history — and he had done it without borrowing a single dime.

While other automakers leaned on Wall Street, Ford kept his company private, funding everything internally — from the Model T assembly lines to the massive River Rouge Plant that became the beating heart of American manufacturing. He refused to take loans, issue stock, or surrender control. Banks offered influence; Ford preferred independence.

His logic was simple but radical: “If you owe the bank $100, that’s your problem. If you owe the bank $100 million, that’s theirs.” He wanted no part of either.

By the 1920s, Ford Motor Company had become a self-contained economic ecosystem — smelting its own steel, producing its own glass, even generating its own electricity. The money that flowed in from every Model T sale didn’t leave the company; it fueled the next invention, the next plant, the next experiment.

And it worked. When the Great Depression crushed competitors drowning in debt, Ford’s privately funded machine kept turning. He could slow production, pay workers, and wait out the storm — all without a single bank call.

So when his heirs discovered hundreds of millions in cash sealed inside the company’s vault, it wasn’t greed. It was the ultimate proof of Ford’s obsession with control — and his defiance of the financial world that once mocked him.

In an age when corporations danced to Wall Street’s tune, Ford marched to his own rhythm — the sound of pistons, progress, and absolute independence.

He didn’t just build cars. He built a new kind of power — one that didn’t need permission.

Would you have trusted your instincts over every banker in America — and been bold enough to fund the future from your own pocket?

View attachment 241437

He knew.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 613

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 351

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 56

- Views

- 5K