-

In Memory of Rebarcock.

As we navigate life without Pat 'Rebarcock.' Flood, who passed on Sept 21, 2025, we continue to remember the profound impact he had on our community. His support was a cornerstone for our forum. We encourage you to visit the memorial thread to share your memories and condolences. In honor of Pat’s love for storytelling, please contribute to his ‘Rebarcock tells a story’ thread. Your stories will help keep his spirit alive among us.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Master Thread Dance Your Cares Away/Fraggle/Law Abiding Citizens

- Thread starter Bryan74b

- Start date

Master Threads.

We are experiencing overwhelming success during this administration.

Great economy. Great foreign policy.

To get more to the point, what we’re are experiencing now is what I expected when I voted for Trump 2x.

Biden has really done a nice job unwinding this situation after decades of apathy by other administrations & Congress.

Orc social media is seething over failures in the area! Slava America! Slava Ukraini!

Generally, the fruits of a presidency are either in their second term, or the next ones admin. Such as Bush and the housing crisis.We are experiencing overwhelming success during this administration.

Great economy. Great foreign policy.

To get more to the point, what we’re are experiencing now is what I expected when I voted for Trump 2x.

In this case, many issues of today are from Biden reversing many of Trumps policies, and of course, the industrial military complex, and or, the deep state.

It is a surprise the economy has not died yet, from hyper inflation due to the COVID money printing scheme.

Fuck Biden. Fuck Trump.

Josh worked for the corporate office of a global, publicly traded company in the south, but his real passion these days was solving crimes that happened two years earlier and hundreds of miles away on Jan. 6, at the U.S. Capitol. Josh’s home sleuthing setup wasn’t anything fancy: just him and his laptop, though he’d switched to a trackball mouse after he started developing symptoms of carpal tunnel “from working my day job all day and hunting insurrectionists by night.”

The halfway mark of the investigation into the Capitol attack — the largest FBI investigation in American history — was fast approaching, and Josh’s community of online sleuths were at the center of it: vacuuming up video, scouring social media, finding fresh faces and new crimes. The FBI was closing in on 1,000 arrests of people who had entered the Capitol or engaged in violence or property destruction that day, and this collection of online investigators — “Sedition Hunters,” they’d branded themselves — had sparked hundreds of those arrests, and aided hundreds more. What’s more, they’d identified more than 700 Jan. 6 participants who had not yet been arrested.

Often, Sedition Hunters like Josh were building entire cases for the FBI from soup to nuts, but the bureau’s rules made it difficult for special agents to offer even basic updates on the status of investigations. The one-way street was frustrating. The best written feedback they could hope for was maybe one word: “received.” One FBI informant was thrilled just to get thumbs-up emojis from her FBI handler.

www.politico.com

www.politico.com

The halfway mark of the investigation into the Capitol attack — the largest FBI investigation in American history — was fast approaching, and Josh’s community of online sleuths were at the center of it: vacuuming up video, scouring social media, finding fresh faces and new crimes. The FBI was closing in on 1,000 arrests of people who had entered the Capitol or engaged in violence or property destruction that day, and this collection of online investigators — “Sedition Hunters,” they’d branded themselves — had sparked hundreds of those arrests, and aided hundreds more. What’s more, they’d identified more than 700 Jan. 6 participants who had not yet been arrested.

Often, Sedition Hunters like Josh were building entire cases for the FBI from soup to nuts, but the bureau’s rules made it difficult for special agents to offer even basic updates on the status of investigations. The one-way street was frustrating. The best written feedback they could hope for was maybe one word: “received.” One FBI informant was thrilled just to get thumbs-up emojis from her FBI handler.

Dating Websites and Furry Forums: The Volunteer Army of Online Investigators Who Helped the FBI Track Down January 6 Perpetrators

How a group of online sleuths tracked down the people who stormed the Capitol on January 6.

Josh worked for the corporate office of a global, publicly traded company in the south, but his real passion these days was solving crimes that happened two years earlier and hundreds of miles away on Jan. 6, at the U.S. Capitol. Josh’s home sleuthing setup wasn’t anything fancy: just him and his laptop, though he’d switched to a trackball mouse after he started developing symptoms of carpal tunnel “from working my day job all day and hunting insurrectionists by night.”

The halfway mark of the investigation into the Capitol attack — the largest FBI investigation in American history — was fast approaching, and Josh’s community of online sleuths were at the center of it: vacuuming up video, scouring social media, finding fresh faces and new crimes. The FBI was closing in on 1,000 arrests of people who had entered the Capitol or engaged in violence or property destruction that day, and this collection of online investigators — “Sedition Hunters,” they’d branded themselves — had sparked hundreds of those arrests, and aided hundreds more. What’s more, they’d identified more than 700 Jan. 6 participants who had not yet been arrested.

Often, Sedition Hunters like Josh were building entire cases for the FBI from soup to nuts, but the bureau’s rules made it difficult for special agents to offer even basic updates on the status of investigations. The one-way street was frustrating. The best written feedback they could hope for was maybe one word: “received.” One FBI informant was thrilled just to get thumbs-up emojis from her FBI handler.

Dating Websites and Furry Forums: The Volunteer Army of Online Investigators Who Helped the FBI Track Down January 6 Perpetrators

How a group of online sleuths tracked down the people who stormed the Capitol on January 6.www.politico.com

Tim Young on GETTR : They use Jill to direct him off stage now...

They use Jill to direct him off stage now...

Atomicglue on GETTR : You can lead a man to data, but you cannot make him think.

You can lead a man to data, but you cannot make him think.

Pfizer slashes revenue estimates as Covid vaccine sales slump

Pfizer had been expecting $67-70 billion in sales, but that number has now dropped to $58-$61 billion.

BREAKING: Antisemitic mob chases down man with Israeli flag during pro-Palestinian London rally

“Khaybar, Khaybar, oh Jews, the army of Mohammed will return.”

MIke Rogers R Al needs to go. Trying to work a deal with dems to keep Jordan out is too much dude.

Your parents owned one of the most successful gas station chains in the world, and you fucking go and put spy cameras in the gas stations, the Airbnb on Lake Travis, and about to find your ass in jail?

Fucking idiot!

Threadreader unroll

Thread by @TheThomasWictor on Thread Reader App

@TheThomasWictor: As the Israeli Operation Swords of Iron against terrorists in Gaza begins, we're seeing the same propaganda put out during Operation Protective Edge (July 8, 2014 – August 26, 2014). Here are some ...…

Zionism must be the NWO Deep State for Israel...

I've often thought this to be the case....

Your parents owned one of the most successful gas station chains in the world, and you fucking go and put spy cameras in the gas stations, the Airbnb on Lake Travis, and about to find your ass in jail?

Fucking idiot!

He could have afforded to pay porn stars to let him film them pee before getting a BJ.

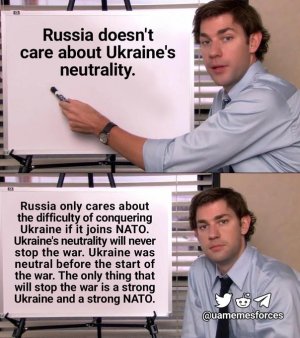

Dumbest shit I’ve heard in a long time, completely false, and in complete opposition of what people on the ground and the well informed know to be true.

Let’s see Russia continue to occupy territory as the years grind on the their KIA climb into the millions!

Slava America! Slava Ukraini!

RFK Jr’s run as an independent has Trump’s team shitting themselves. The vaccine could easily sink him which would be pretty hilarious given how hard his base bit down on that communist propaganda.

www.politico.com

www.politico.com

Kennedy family feud cools as RFK Jr.'s independent run rattles Republicans

The stalwart Democratic family had been pressuring Kennedy for months to drop out.

Her:I've only been with a few guys

Me:

Me:

I found @Jake’s Ho Stan’s OnlyFans account.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 13

- Views

- 614

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 353

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 56

- Views

- 5K