Surely some of you dipshits fell for this. Really hoping I’m not the only one but it’s gonna be a great résumé builder and gave me some great ideas for my next startup.

Best Job Ever

The Zoom call had about 40 people on it - or that's what the people who had logged on thought. The all-staff meeting at the glamorous design agency had been called to welcome the growing company's newest recruits. Its name was Madbird and its dynamic and inspirational boss, Ali Ayad, wanted everyone on the call to be ambitious hustlers - just like him.

But what those who had turned on their cameras didn't know was that some of the others in the meeting weren't real people. Yes, they were listed as participants. Some even had active email accounts and LinkedIn profiles. But their names were made up and their headshots belonged to other people.

The whole thing was fake - the real employees had been "jobfished". The BBC has spent a year investigating what happened.

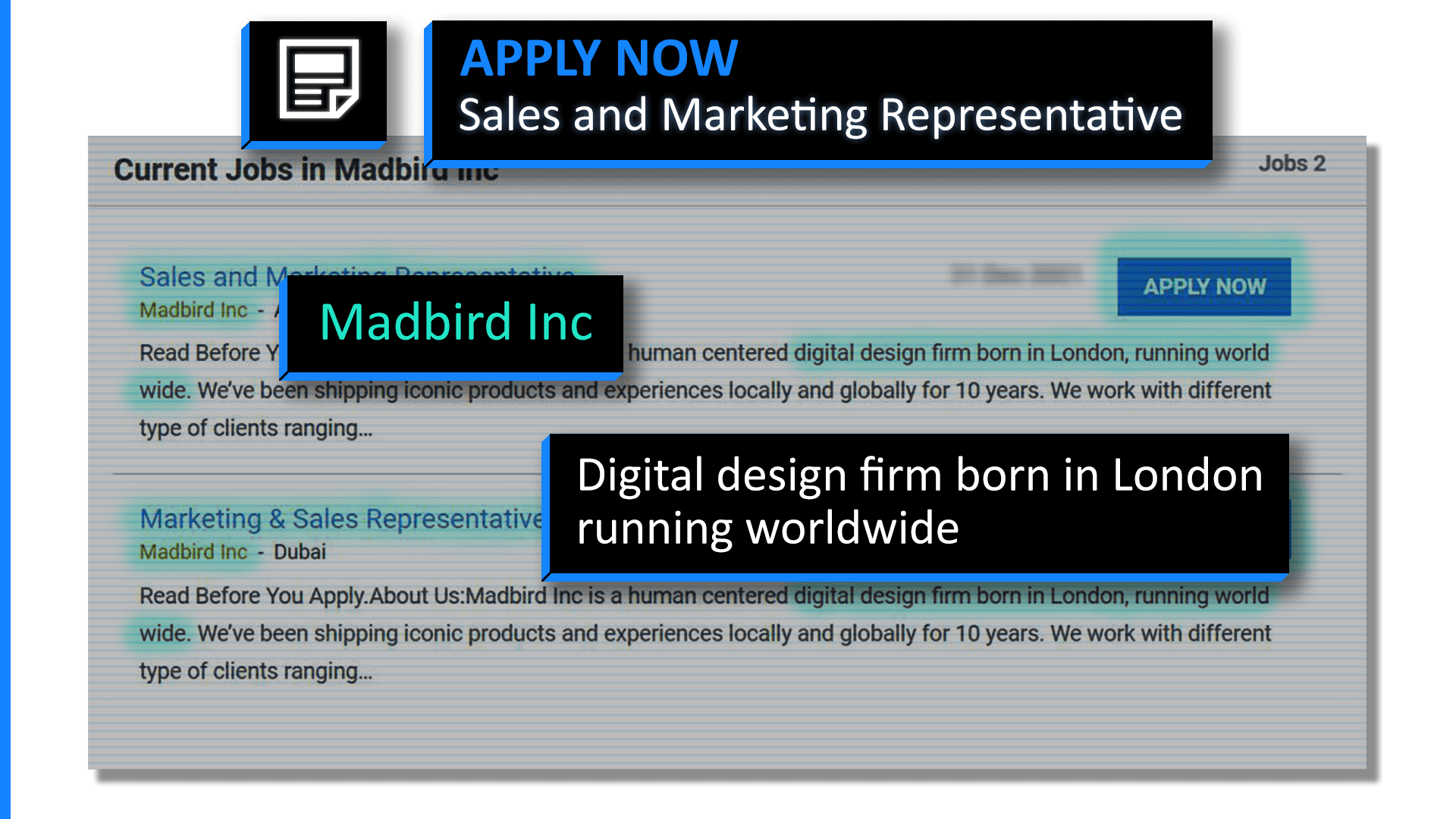

Chris Doocey, a 27-year-old sales manager based in Manchester, started at Madbird in October 2020, a few months before the Zoom call. He would be working from home, but the pandemic was still raging, so that was normal. Covid had upended Chris's life. It had cost him his last job and was the reason he'd applied for this role at Madbird. The ad described a "human-centred digital design agency born in London, running worldwide". It sounded good.

Madbird hired more than 50 others. Most worked in sales, some in design and some were brought in to supervise. Every new joiner was instructed to work from home - messaging over email and speaking to each other on Zoom.

Days were often long. Jordan Carter from Suffolk, who was 26 at the time, was credited with being one of the hardest working members of Chris's sales team. In five months, he pitched Madbird to 10,000 possible business clients, hoping to win deals to redesign websites or build apps. By January 2021, his work ethic had earned him the title Employee of the Month.

Other staff lived outside the UK. Keen to tap into a global market, Madbird's HR department posted job ads online for an international sales team based out of Dubai. At least a dozen people from Uganda, India, South Africa, the Philippines and elsewhere were hired.

Image caption,

Job adverts were placed for Madbird teams in London and Dubai

For them, the job represented more than just a pay cheque - but a UK visa too. If they passed their six-month probation period, and met their sales targets, their contracts said Madbird would sponsor them to move to the UK.

Ali Ayad knew what it could mean to make a new life in the UK. He often talked to Madbird staff about his past before settling in London. But there were many versions of his story.

To one person he introduced himself as a Mormon, from Utah in the US. To others, he was from Lebanon, where a difficult childhood had taught him how to be a hustler. Even his name changed. Sometimes he added a second "y" to his surname, spelling it "Ayyad". Other times he signed off as "Alex Ayd".

But some chapters in the story he told people were consistent. Key - above all - was the time he spent as a creative designer at Nike. He told everyone about working at the fashion brand's Oregon headquarters in the US. It was where he'd met Dave Stanfield, Madbird's co-founder.

The stories about Ali's high-flying career didn't seem far-fetched. He was a smooth operator on video calls - intense, charismatic, even appearing caring. He spoke with confidence, sometimes bordering on bullishness. It is how he persuaded at least three people to quit other jobs to work for him.

IMAGE SOURCE,INSTAGRAM

IMAGE SOURCE,INSTAGRAM

Image caption,

Ali Ayad has over 90,000 followers on his Instagram - in his bio he describes himself as an "influencer"

Madbird's staff had no reason to doubt Ali's Nike stories. And if they did, all they had to do was check his LinkedIn profile. It glowed with lengthy endorsements from former colleagues.

Ali Ayad "floored me with how meaningful and thoughtful his approach was", read one comment - supposedly from a creative director at Nike. "Agencies can be filled with copycats but that's not Ali. He brings originality and authenticity to any project he works on."

And then there was his business partner, Dave Stanfield. At Nike, Ali Ayad was "instrumental" and "one of the best professionals I've ever worked with," read his testimony.

Ali's optimism and energy were contagious. One person he hired compared her new boss to Tom Cruise. But the two people whom Ali compared himself to most often were Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. The tech titans were Ali's idols.

"Elon Musk works 16 hours a day, I'm trying to do 17!" he wrote in one email trying to motivate his team to keep pushing through. And - weighing up another tough business decision - he used a quote often attributed to Steve Jobs. "If you want to make everybody happy, don't be a leader, go sell ice cream."

For months, Madbird's daily business hummed along, more designers were hired to meet the backlog of briefs being negotiated by the sales team.

But even before the truth about Madbird was revealed, its workers had a problem. Because of the unusual way their contracts had been written, they were yet to be paid.

Reporter Catrin Nye exposes Ali Ayad's tangled web of lies and ends up confronting him to get to the truth.

Watch Jobfished on 21 February at 21:00 on BBC Three or BBC iPlayer.

They had all agreed to work on a commission-only basis for the first six months. It was only after they passed their probation period that they would be put on a salary - about £35,000 ($47,300) for most. Until then, they would only earn a percentage of every deal they negotiated. They were all young adults looking for work and living through a pandemic. Many felt they had no choice but to accept the terms in their contracts.

But no deals were ever finalised. By February 2021, not a single client contract had been signed. None of the Madbird staff had been paid a penny.

Some recruits ended up leaving after a few weeks, but many stayed. Many had been there for almost six months - forced to take out credit cards and borrow money from family to keep on top of bills.

The longer you worked at Madbird, the harder it became to leave. What if one of the big deals you'd been working on came through next week? It made no sense to resign just as you were about to finish your probation period. For many, a salary seemed within grasp. Plus, in the middle of the pandemic, jobs were hard to find.

It is obvious now why no-one was paid. Madbird had no money coming in. But that wasn't obvious to new staff. They mistakenly assumed their pay contracts were unique - and that their line managers must have been on salaries. Besides, Madbird was on the cusp of signing a whole bunch of deals. The money was finally coming.

Or that is how it appeared until everything crumbled one afternoon.

Image caption,

Gemma Brett became suspicious soon after she started working for Madbird

Gemma Brett, a 27-year-old designer from west London, had only been working at Madbird for two weeks when she spotted something strange.

Curious about what her commute would be like when the pandemic was over, she searched for the company's office address. The result looked nothing like the videos on Madbird's website of a sleek workspace buzzing with creative-types. Instead, Google Street View showed an upmarket block of flats in London's Kensington.

Gemma contacted an estate agent with a listing at the same address who confirmed her suspicion - the building was purely residential. We later corroborated this by speaking to someone who'd worked in the building for years. They had never seen Ali Ayad. The block of flats was not the global headquarters of a design firm called Madbird.

Gemma shared her discovery with another Madbird employee she had got to know and trust - Antonia Stuart, who was leading the company's expansion into Dubai.

Image caption,

Antonia Stuart was hired to work as Madbird's head of creative based in Dubai

Using online reverse image searches they dug deeper. They found that almost all the work Madbird claimed as its own had been stolen from elsewhere on the internet - and that some of the colleagues they'd been messaging online didn't exist.

They thought about their options. One was to leave quietly without causing a stir. They had no idea who was behind this con, or the scale of it. They were scared. On the other hand, they worried if the truth wasn't exposed innocent staff could end up in trouble if they completed deals for Madbird based on lies. Deals were just days away.

In the end, they decided to send an all-staff email from an alias - Jane Smith.

The

Best Job Ever

The elaborate con that tricked dozens into working for a fake design agency

The Zoom call had about 40 people on it - or that's what the people who had logged on thought. The all-staff meeting at the glamorous design agency had been called to welcome the growing company's newest recruits. Its name was Madbird and its dynamic and inspirational boss, Ali Ayad, wanted everyone on the call to be ambitious hustlers - just like him.

But what those who had turned on their cameras didn't know was that some of the others in the meeting weren't real people. Yes, they were listed as participants. Some even had active email accounts and LinkedIn profiles. But their names were made up and their headshots belonged to other people.

The whole thing was fake - the real employees had been "jobfished". The BBC has spent a year investigating what happened.

Chris Doocey, a 27-year-old sales manager based in Manchester, started at Madbird in October 2020, a few months before the Zoom call. He would be working from home, but the pandemic was still raging, so that was normal. Covid had upended Chris's life. It had cost him his last job and was the reason he'd applied for this role at Madbird. The ad described a "human-centred digital design agency born in London, running worldwide". It sounded good.

Madbird hired more than 50 others. Most worked in sales, some in design and some were brought in to supervise. Every new joiner was instructed to work from home - messaging over email and speaking to each other on Zoom.

Days were often long. Jordan Carter from Suffolk, who was 26 at the time, was credited with being one of the hardest working members of Chris's sales team. In five months, he pitched Madbird to 10,000 possible business clients, hoping to win deals to redesign websites or build apps. By January 2021, his work ethic had earned him the title Employee of the Month.

Other staff lived outside the UK. Keen to tap into a global market, Madbird's HR department posted job ads online for an international sales team based out of Dubai. At least a dozen people from Uganda, India, South Africa, the Philippines and elsewhere were hired.

Image caption,

Job adverts were placed for Madbird teams in London and Dubai

For them, the job represented more than just a pay cheque - but a UK visa too. If they passed their six-month probation period, and met their sales targets, their contracts said Madbird would sponsor them to move to the UK.

Ali Ayad knew what it could mean to make a new life in the UK. He often talked to Madbird staff about his past before settling in London. But there were many versions of his story.

To one person he introduced himself as a Mormon, from Utah in the US. To others, he was from Lebanon, where a difficult childhood had taught him how to be a hustler. Even his name changed. Sometimes he added a second "y" to his surname, spelling it "Ayyad". Other times he signed off as "Alex Ayd".

But some chapters in the story he told people were consistent. Key - above all - was the time he spent as a creative designer at Nike. He told everyone about working at the fashion brand's Oregon headquarters in the US. It was where he'd met Dave Stanfield, Madbird's co-founder.

The stories about Ali's high-flying career didn't seem far-fetched. He was a smooth operator on video calls - intense, charismatic, even appearing caring. He spoke with confidence, sometimes bordering on bullishness. It is how he persuaded at least three people to quit other jobs to work for him.

Image caption,

Ali Ayad has over 90,000 followers on his Instagram - in his bio he describes himself as an "influencer"

Madbird's staff had no reason to doubt Ali's Nike stories. And if they did, all they had to do was check his LinkedIn profile. It glowed with lengthy endorsements from former colleagues.

Ali Ayad "floored me with how meaningful and thoughtful his approach was", read one comment - supposedly from a creative director at Nike. "Agencies can be filled with copycats but that's not Ali. He brings originality and authenticity to any project he works on."

And then there was his business partner, Dave Stanfield. At Nike, Ali Ayad was "instrumental" and "one of the best professionals I've ever worked with," read his testimony.

Ali's optimism and energy were contagious. One person he hired compared her new boss to Tom Cruise. But the two people whom Ali compared himself to most often were Steve Jobs and Elon Musk. The tech titans were Ali's idols.

"Elon Musk works 16 hours a day, I'm trying to do 17!" he wrote in one email trying to motivate his team to keep pushing through. And - weighing up another tough business decision - he used a quote often attributed to Steve Jobs. "If you want to make everybody happy, don't be a leader, go sell ice cream."

For months, Madbird's daily business hummed along, more designers were hired to meet the backlog of briefs being negotiated by the sales team.

But even before the truth about Madbird was revealed, its workers had a problem. Because of the unusual way their contracts had been written, they were yet to be paid.

Reporter Catrin Nye exposes Ali Ayad's tangled web of lies and ends up confronting him to get to the truth.

Watch Jobfished on 21 February at 21:00 on BBC Three or BBC iPlayer.

They had all agreed to work on a commission-only basis for the first six months. It was only after they passed their probation period that they would be put on a salary - about £35,000 ($47,300) for most. Until then, they would only earn a percentage of every deal they negotiated. They were all young adults looking for work and living through a pandemic. Many felt they had no choice but to accept the terms in their contracts.

But no deals were ever finalised. By February 2021, not a single client contract had been signed. None of the Madbird staff had been paid a penny.

Some recruits ended up leaving after a few weeks, but many stayed. Many had been there for almost six months - forced to take out credit cards and borrow money from family to keep on top of bills.

The longer you worked at Madbird, the harder it became to leave. What if one of the big deals you'd been working on came through next week? It made no sense to resign just as you were about to finish your probation period. For many, a salary seemed within grasp. Plus, in the middle of the pandemic, jobs were hard to find.

It is obvious now why no-one was paid. Madbird had no money coming in. But that wasn't obvious to new staff. They mistakenly assumed their pay contracts were unique - and that their line managers must have been on salaries. Besides, Madbird was on the cusp of signing a whole bunch of deals. The money was finally coming.

Or that is how it appeared until everything crumbled one afternoon.

Image caption,

Gemma Brett became suspicious soon after she started working for Madbird

Gemma Brett, a 27-year-old designer from west London, had only been working at Madbird for two weeks when she spotted something strange.

Curious about what her commute would be like when the pandemic was over, she searched for the company's office address. The result looked nothing like the videos on Madbird's website of a sleek workspace buzzing with creative-types. Instead, Google Street View showed an upmarket block of flats in London's Kensington.

Gemma contacted an estate agent with a listing at the same address who confirmed her suspicion - the building was purely residential. We later corroborated this by speaking to someone who'd worked in the building for years. They had never seen Ali Ayad. The block of flats was not the global headquarters of a design firm called Madbird.

Gemma shared her discovery with another Madbird employee she had got to know and trust - Antonia Stuart, who was leading the company's expansion into Dubai.

Image caption,

Antonia Stuart was hired to work as Madbird's head of creative based in Dubai

Using online reverse image searches they dug deeper. They found that almost all the work Madbird claimed as its own had been stolen from elsewhere on the internet - and that some of the colleagues they'd been messaging online didn't exist.

They thought about their options. One was to leave quietly without causing a stir. They had no idea who was behind this con, or the scale of it. They were scared. On the other hand, they worried if the truth wasn't exposed innocent staff could end up in trouble if they completed deals for Madbird based on lies. Deals were just days away.

In the end, they decided to send an all-staff email from an alias - Jane Smith.

The

Last edited: